Listen to this Museletter

Introduction

The UAE has become the modern Atlantis and a junction of the world’s silk routes. The worlds of geopolitics, commerce, technology, art, and spirituality intersect here, weaving a panoramic vision of what an ideal modern civilisation could be.

Most nations inherit their structure—geography defines trade, history shapes governance, and natural resources determine economic fate. The UAE had some of that, but not enough to depend on. No rivers. No fertile hinterland. No legacy institutions. Just a cluster of sheikhdoms forged out of necessity, where survival—not scale—was the starting point. Its geography was strategic, but its early economy was fragile. What it lacked in inheritance, it made up for in intentionality.

But here’s what changed everything: the UAE didn’t just react to opportunity—it engineered it. What began as a maritime hustle became a globally choreographed playbook. One where tourism wasn’t a byproduct but a wedge. Where finance wasn’t outsourced but made sovereign. Where education became infrastructure, and R&D became industry. Where world-class infrastructure, the skyline and Burj Khalifa included, was not just a real estate play, but a platform for financial experts, tech innovators, and creatives to build a global scale.

This wasn’t a linear transition from oil to diversification. It was the deliberate construction of an economic engine—with each phase igniting new drivers of capital, talent, and legitimacy to power the next. The sequencing wasn’t random—it was intentional.

This piece breaks that evolution down in four decisive arcs —each representing a strategic ignition point in the UAE’s sovereign development engine:

- Phase 1: In the post-oil era, tourism and transit leveraged geography to place the UAE on the global map and convert visibility into soft power.

- Phase 1.5: Finance created a parallel capital regime, grounded in trust, rule of law, and institutional clarity.

- Phase 2: Land and education were converted into long-term assets and institutional capability—anchoring human capital and investable infrastructure.

- Phase 3: DeepTech, National Security, and Local Industrial Systems are becoming pillars of the UAE’s sovereign technology stack—signalling a strategic shift from buyer to builder, underpinned by new institutional and regulatory frameworks.

What follows is not just a timeline of transformation—but a structural breakdown of how the UAE built a multi-cylinder economic engine, increasingly powered by sovereign autonomy, institutional design, and long-term intent.

Museletter Highlights:

- Agna Insights

Read about how the UAE Engineered Its Economic Sovereignty - Agna Updates

Our LinkedIn updates and team engagements from Agna

Agna Insights

From Desert to DeepTech:

How the UAE Engineered Its Economic Sovereignty

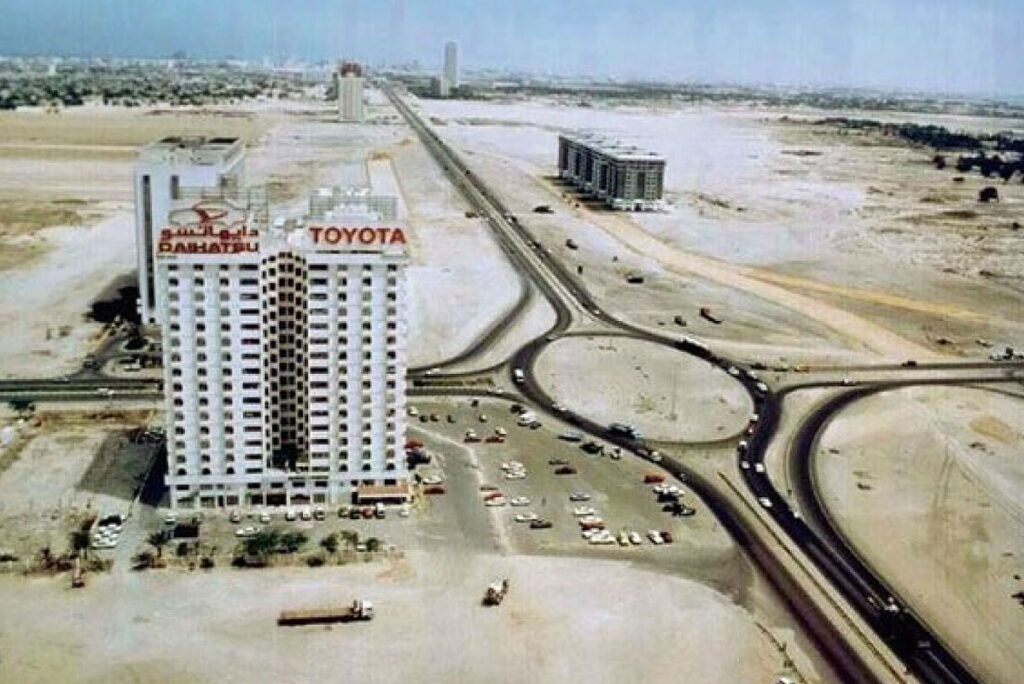

Introduction: Before Oil, There Was Trade—and Survival

Long before the glass towers, the UAE was a cluster of loosely allied tribes spread across seven emirates—then known as the Trucial States (a group of sheikhdoms under British protection from the 19th century until 1971)— each with distinct strengths but a shared challenge: survival. The terrain was unforgiving—desert inland, hostile waters offshore, and little arable land. But adversity bred ingenuity. Trade routes from Africa, Persia, and India converged here, linking the Gulf to broader Indian Ocean commerce. Maritime trade in pearls, spices, and dates made Dubai and Sharjah important ports, while Al Ain’s falaj irrigation systems sustained small-scale agriculture in the desert. The inland Bani Yas tribes herded camels and cultivated date palms, while coastal tribes like the Al Bu Falasah navigated the Gulf with intimate knowledge of winds and tides.

This wasn’t an economy; it was a hustle, a survival pact with the land. Then came oil, which transformed the Emirates.

The Engine: From Survival to Sovereignty

The UAE’s economic evolution wasn’t linear. It wasn’t a cycle. It was a designed engine—a system of interlocking drivers, each activated at strategic inflexion points, each still running today.

Each phase generated surplus capital, talent, and access that funded the next. And every phase was built with intent: transforming a vulnerability into an advantage. The sequence wasn’t accidental. It was engineered to scale capacity, not just capability.

Phase 1:

Tourism Economy – Turning Geography into a Gateway

Timeline: 1980s–2005

Inputs: Location, stability, and early aviation

Outputs: Brand, global inflows, soft power

Dubai had no oil windfall like Abu Dhabi. Its reserves were modest and peaked early, which created a sense of urgency rather than complacency. By the 1980s, Dubai’s strategy started to take shape: leverage its geography, political neutrality, and logistics potential to become a global transit and lifestyle hub.

Emirates Airlines, launched in 1985 with just two aircraft and a USD 10M seed investment, wasn’t merely a commercial bet—it was a soft power play. By the early 2000s, Emirates had grown into a world-class carrier, connecting East and West and capitalising on Dubai’s unique time-zone overlap with Asia, Europe, and Africa. The airline became a key instrument of nation branding, positioning Dubai on the global map.

Tourism was the hook, but not a byproduct. It was engineered. From the Burj Al Arab’s iconic silhouette to Palm Jumeirah’s reclaimed coastline, from Mall of the Emirates’ indoor ski slope to the early vision for the Burj Khalifa—every development was conceived as both infrastructure and international statement, symbols of global relevance. These weren’t superficial indulgences; they were early-stage drivers in the broader engine of soft power and mobility.

The UAE prioritised movement before markets—built airports and airlines before IPO pipelines. What came first was flow: of people, stories, and attention. Transit wasn’t an accessory; it was a core ignition point in the national growth engine.

Stats & Indicators:

Phase 1.5:

The Finance Economy – Building a Sovereign Capital Interface

Timeline: 2000–2015

Inputs: Global attention, tourism surplus, legal-financial reforms to build institutional trust

Outputs: Capital intermediation, free zones, institutional trust

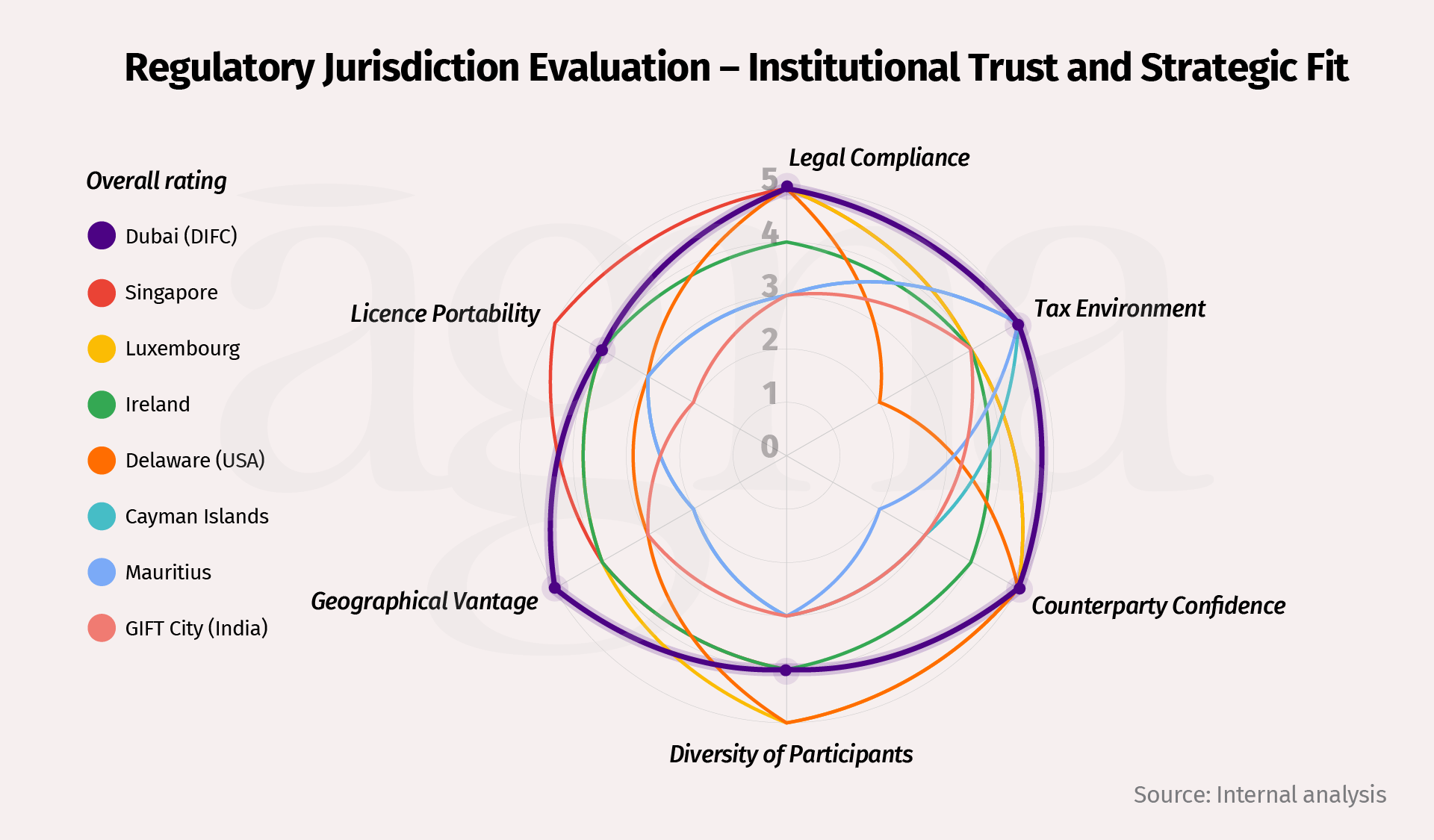

While tourism brought the world to Dubai, the question emerged: could capital be just as mobile as people? The next phase activated a new driver in the UAE’s economic engine—legal-financial zones designed to embed global trust, attract capital, and sustain institutional credibility. DIFC became the institutional embodiment of that answer.

Launched in 2004, the Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC) was more than a free zone—it was a parallel legal and regulatory system, based on English common law, with its courts, commercial code, and financial regulator (DFSA). It was designed to bridge East–West finance by offering regulatory certainty and tax neutrality in a volatile region. Today, DIFC also serves as a key institutional pillar of the Dubai Economic Agenda (D33), which seeks to position Dubai among the world’s top four financial centres by 2033, with finance as a core engine of economic growth.

Other capital zones followed this:

- DMCC (Dubai Multi Commodities Centre, 2002) catalysed trade in gold, diamonds, and crypto.

- ADGM (Abu Dhabi Global Market, 2015) extended the same common-law financial structure to the capital, with a strategic focus on asset management and fintech.

- RAKEZ, KIZAD, Masdar Free Zone and others diversified economic specialisation across the Emirates.

Together, these created a lattice of economic zones that attracted:

- Family offices and hedge funds

- Corporate HQs and asset managers

- Commodity traders, crypto firms, and sovereign LPs

They transformed land into regulated zones of capital movement, and the UAE into a regional financial nerve centre. Finance became not just a layer of the economy, but a parallel driver, deeply embedded in the long-term structure of the engine.

Stats & Indicators:

- DIFC closed 2024 with 6,920 active companies and record results in its 20th anniversary year, reinforcing Dubai’s role as the region’s financial hub. (Source).

- By Q1 2025, ADGM counted 2,781 operational entities (+43% YoY) and AUM up 33% year‑on‑year—sustaining momentum from a record-breaking 2024. (Source)

- DMCC is the world’s #1 free zone, housing 25,000+ companies. (Source)

- With 45+ Free Trade Zones, the UAE ranks #1 in the MENA region for investment attractiveness and ease of doing business. (Source)

Phase 2:

Knowledge & Real Estate Economy – Converting Land into Capital, and Capital into Skill

Timeline: 2005–2020

Input: Tourism surplus, safe haven appeal

Output: Urban capital markets, institutional education, policy architecture

Let’s break this down.

Tourism brought global attention and inflow. But attention alone doesn’t anchor and compound value. In this phase, the UAE added two more strategic cylinders to its economic engine: real estate as capital infrastructure, and education as a platform for long-term capability.

Real Estate as a Capital Strategy

Dubai led with a bold experiment: in 2002, it introduced freehold property rights for foreigners—a rare move in the region. This marked a shift from state-managed access to open market ownership—real estate became investable, tradable, and globally visible.

The logic wasn’t just housing—it was financialisation. With off-plan sales, escrow regulation, REIT frameworks, and mortgage instruments, the UAE built an urban capital market as part of its economic engine, where land became a mechanism for global inflow and residency strategy.

Dubai’s skyline reflected this shift, with Downtown Dubai, Palm Jumeirah, Business Bay, JVC, and later Dubai Hills becoming magnets for international capital.

Abu Dhabi mirrored this with master-planned zones like Al Reem Island, Al Raha Beach, and Saadiyat Island, offering cultural, residential, and high-yield investment blends.

Sharjah and the northern emirates focused on affordable housing and industrial real estate, catering to SMEs and regional middle classes.

Together, these shifts turned the UAE into a real estate sovereign, with property contributing significantly to GDP, tradeable financial products, and anchoring long-term residency.

This part of the UAE’s economic engine, once driven by bold regulatory shifts, now underpins future-facing strategies—most notably Dubai’s D33 Agenda, RAK’s Vision 2030 Agenda and the federal We the UAE 2031 vision. These initiatives recast real estate as a tool for economic competitiveness, global capital integration, and long-term residency.

Knowledge as Capability Infrastructure

In parallel with real estate, the UAE began treating knowledge as sovereign infrastructure—not just a public good, but a strategic lever for capability-building and long-term autonomy.

Global institutions like NYU Abu Dhabi, Sorbonne Abu Dhabi, and RIT Dubai weren’t just educational outposts; they were positioned as talent anchors, embedded in curated urban districts. Saadiyat Island in Abu Dhabi fused higher education with cultural capital. University City in Sharjah consolidated over a dozen institutions into a regional academic hub. Dubai Knowledge Park and Academic City anchored private-sector learning and vocational skilling.

These campuses were paired with applied innovation zones:

- in5 (Dubai) supported early-stage founders;

- Hub71 (Abu Dhabi) attracted funded tech startups and VCs;

- Masdar City combined cleantech research with sustainable urbanism.

Toward the late 2010s, this base matured into state-backed R&D institutions focused on deep technologies:

- MBZUAI, launched in 2019, became the world’s first AI-focused graduate university, marking the UAE’s pivot from knowledge hosting to IP creation in artificial intelligence.

- Khalifa University, Masdar Institute, and the Emirates Scientists Council expanded applied science capability across energy, aerospace, and health-tech.

- Mohammed bin Rashid Space Centre (MBRSC) and the UAE Space Agency laid the foundation for sovereign space programs and STEM-intensive talent development.

- Dubai Future District, Dubai Future Labs, and the Dubai Innovation Hub brought public-private prototyping, foresight, and exponential technology testing into the heart of the economy.

- In 2020, Technology Innovation Institute (TII) was launched in Abu Dhabi to consolidate R&D efforts in AI, space, quantum, cryptography, robotics, and advanced materials, bridging basic science and national tech priorities.

Framing this institutional buildout is the National Advanced Sciences Agenda 2031, launched in 2018, which reinforces the pivot from knowledge hosting to sovereign innovation by prioritising homegrown research in health, energy, and advanced technology.

Together, these institutions formed the intellectual and capability infrastructure that would sustain the transition from a knowledge economy to an innovation-driven industrial economy, grounded in research, talent pipelines, and sovereign IP ambitions— each becoming a running component in the larger national engine.

Stats & Indicators:

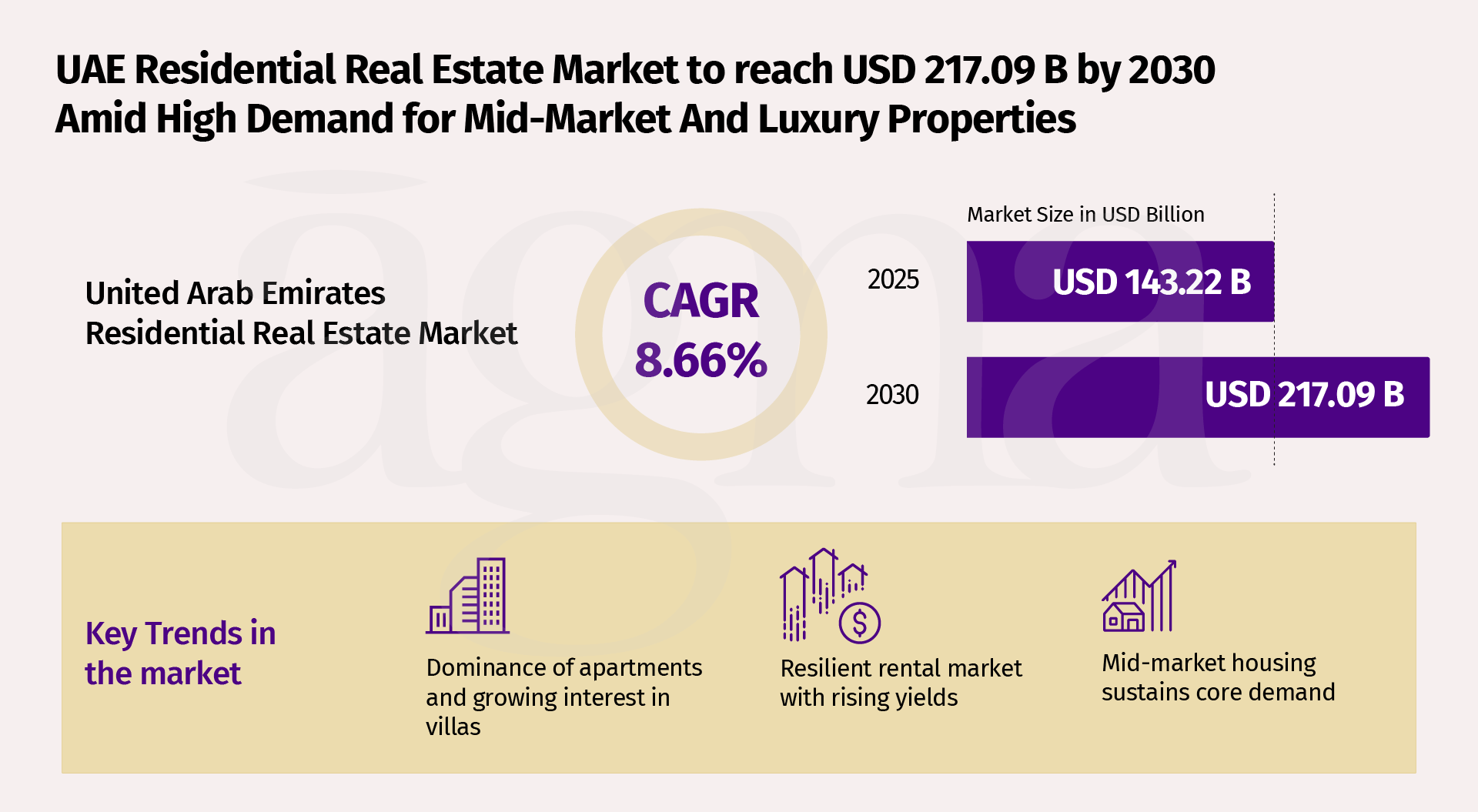

- Dubai recorded USD 117B in real estate deals in H1 2025—a new high—driven by visa reforms, foreign ownership, and diverse global investors (Source)

- The UAE residential real estate market is currently estimated at USD 143.22B in 2025, on track to reach USD 217.09B by 2030, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.7%. (Source)

- Hub71 alone has over 250 startups with USD 2.17B+ in total funding raised. (Source)

- UAE ranks #1 regionally in the Global Talent Competitiveness Index (INSEAD, 2023).

Phase 3:

The Tech & Industrial Economy – From Buyer to Builder

Timeline: 2020 onward

Inputs: Capital base, National R&D infra, sovereign scale

Outputs: Industrial innovation, National Security-linked autonomy & IP stack.

By the early 2020s, the UAE’s knowledge economy had laid the institutional groundwork, with universities, research hubs, free zones, and talent policies in place. What followed was a decisive national pivot: from building individual initiatives to assembling a fully integrated economic engine, designed to power sovereign innovation and industrial growth. This phase marked the beginning of the UAE’s transformation from a technology importer to a strategic producer, with a clear ambition not only to diversify but to attain sovereign control over critical technologies and supply chains.

This transition is being guided by a coordinated set of national strategies launched over the past decade to synchronise innovation, industrial capacity, and sovereign capability:

- UAE AI Strategy 2031 (launched 2017) – establish global leadership in artificial intelligence

- Operation 300Bn (launched 2021) – increase industrial sector’s contribution to GDP

- UAE Net Zero by 2050 (announced 2021) – lead climate and clean-tech innovation

- National Space Strategy 2030 (launched 2019) – develop sovereign space capabilities

- Digital Economy Strategy 2031 (launched 2022) – double the digital economy’s GDP share

- National Advanced Sciences Agenda 2031 (launched 2018) – enhance national scientific readiness

- Dubai Economic Agenda (D33) (launched 2023) – double Dubai’s economy by 2033 and establish it as one of the top 3 cities to invest, live, and work in.

These strategies are now being executed through a cohesive institutional ecosystem. Entities such as EDGE Group and G42 serve as foundational components within the UAE’s sovereign innovation architecture, operating in alignment with research and policy institutions including MBZUAI, Masdar, TII, ATRC and Khalifa University. Together, they constitute the operational core advancing the UAE’s DeepTech, dual-use, and frontier technology objectives.

At the centre of this transition is artificial intelligence and digital infrastructure. While MBZUAI laid the academic foundation in Phase 2, this phase is seeing its alignment with national economic missions. G42 has expanded into health, finance, and public sector platforms, deploying AI models trained on sovereign compute infrastructure, built through strategic partnerships with OpenAI, Cerebras, AWS, and Microsoft Azure. AI is no longer a research pursuit—it is becoming a core driver of national productivity. According to PwC, AI alone is projected to contribute over 14% to UAE GDP by 2030.

In digital assets and blockchain, the UAE positioned itself as a global jurisdictional pioneer. VARA, the world’s first dedicated virtual assets regulator, was established in Dubai. DIFC and ADGM activated regulatory sandboxes to pilot tokenisation and decentralised finance. The Central Bank’s Digital Dirham initiative, alongside participation in the BIS-led Project mBridge, underscored the UAE’s commitment to shaping future-ready financial rails. These initiatives are reinforced by national strategies like UAE Pass and the Emirates Blockchain Strategy, embedding blockchain across smart governance and digital identity infrastructure.

In defence and aerospace, early R&D is maturing into full-spectrum industrial platforms. EDGE Group, founded in 2019, has become one of the world’s top 25 defence suppliers, producing loitering munitions, drone systems, jammers, and autonomous vehicles. Meanwhile, MBRSC’s Hope Probe reached Mars in 2021, making the UAE the first Arab nation to enter Mars orbit. The UAE’s space ambitions are expanding with lunar missions, Earth observation constellations, and satellite manufacturing, supported by the UAE Space Agency and the AED 3B (~USD 817M) National Space Fund.

Supporting this build-up is a deeper institutional architecture. The Advanced Technology Research Council (ATRC), launched in 2020, serves as Abu Dhabi’s apex R&D body. Through TII and ASPIRE, ATRC is channelling funding into quantum computing, cryptography, autonomous systems, and robotics. TII, seeded in Phase 2, is evolving into a platform for dual-use R&D translation.

The Tawazun Council, restructured in 2022, functions as the UAE’s strategic procurement and industrial development authority for defence and security. It oversees acquisitions, manages the Tawazun Economic Program (industrial offsets), and supports joint ventures with OEMs and dual-use startups—bridging state needs and private sector capabilities.

In sustainability, the UAE has shifted from investment to industrial execution. Masdar is scaling renewable energy, green hydrogen, and carbon capture initiatives. The UAE Net Zero by 2050 strategy is accelerating innovation in storage, clean materials, and urban sustainability—supported by research from TII, Khalifa University, and global clean-tech partners.

In life sciences, the UAE is progressing toward bio-sovereignty. G42 Healthcare, Hayat Biotech, and M42 have advanced genomics, diagnostics, and vaccine production. The Emirati Genome Program is entering clinical application, supported by digital health infrastructure and regulatory frameworks. The UAE is investing across the full life sciences stack—from mRNA manufacturing to AI-powered trials.

Key Stats & Indicators:

- EDGE ranks among the world’s top 25 military suppliers by revenue (Source)

- G42 launched a USD 10B expansion fund, cementing its role in building cross-border AI ecosystems through strategic partnerships with OpenAI, Cisco, and sovereign entities (Source)

- AI projected to contribute 14%+ to UAE GDP by 2030 (PwC) (Source)

- VARA’s 2022 launch positioned Dubai among the world’s first fully regulated virtual-asset jurisdictions outside traditional financial zones.

Structural Levers Powering the Sovereign Stack

While each phase of the UAE’s economic evolution activated new domains—Tourism in Phase 1, Finance in Phase 1.5, Real Estate and Education in Phase 2, and Frontier Tech and Industrial innovation in Phase 3—these domains were never retired. Like cylinders in a well-tuned engine, they continue to operate in sync, generating capital, talent, and institutional momentum.

The sovereign engine is sustained by three foundational levers—each structured not just to support, but to accelerate:

- People:

From hospitality to high science, talent has remained the constant. Strategic mobility policies (Golden Visa, Remote Work Visa) made the UAE a magnet for global founders, operators, and researchers. What began as tourism talent in Phase 1 matured into a diverse, high-skill workforce, aligned through dual-language fluency and targeted incentives. - Capital:

In Phase 1.5, capital became sovereign. Today, sovereign wealth funds like Mubadala, ADIA, ADQ, and ICD act as co-builders, not just allocators—embedding capital into national innovation arcs. Fund managers and family offices in DIFC and ADGM operate as institutional gears across the MENASA corridor, enabling scale in every economic domain. - Infrastructure:

From airport terminals to AI clusters, infrastructure has always been the physical chassis of the engine. What began with world-class tourism and urban development in Phases 1 and 2 now supports the demands of Phase 3—sovereign AI compute (G42, AWS, Cerebras), biomanufacturing (Hayat Biotech), and space autonomy (MBRSC, UAE Space Agency). This infrastructure is no longer passive—it’s programmable, adaptive, and built for sovereignty.

Why the UAE Is Different—and Why It Works

Other nations succeeded by doubling down on a single existential edge. The UAE, by contrast, is synchronising sovereign investments across National Security, AI, life sciences, clean energy, and space—not incrementally, but with speed, scale, and institutional clarity.

Its neutrality, world-class infrastructure, and founder-friendly mobility policies make it a global magnet. But what truly sets it apart is its state-led capital orchestration, its strategic geography as a corridor between East and West, its sovereign-backed innovation ecosystems, and its willingness to incubate dual-use frontier tech at scale.

Equally significant is the UAE’s commitment to safety, respect for diverse cultures, and legal frameworks that support long-term stability. It offers expatriates the right to own freehold property, underlining a system that values permanence over transience. This cultural openness and legal clarity create an environment where both individuals and capital feel secure.

This is not just diversification. It’s sovereign capability construction, and it’s what makes the UAE a central actor in shaping the future economy.

Agna’s Role: Built for This Inflexion

This moment isn’t just about receiving approval. It marks the activation of a system we’ve built with purpose. With the Fund Manager licence from the Dubai Financial Services Authority (DFSA), Agna moves from setup to full execution, operating within the same financial framework that powered the UAE’s Phase 1.5 transformation. That phase was never just about opening markets. It was about building trust, legal clarity, and institutions that attract long-term capital.

DIFC was a strategic choice, aligned with how we operate and what we aim to build. More than a location, it is a platform that enables action. It offers legal certainty, global counterparty access, and a strong foundation for cross-border execution. Over the past two decades, it has anchored a dense and functional ecosystem: home to 20 of the top 25 global banks, 5 of the top 10 insurers, and 5 of the top 10 asset managers. More than $1 trillion in private wealth is now managed from the region. DIFC ranks among the global top 10 for infrastructure competitiveness and sits within a broader regulatory environment that includes over 45 free zones across the UAE, all offering full foreign ownership and deep regulatory flexibility.

What the UAE built at a sovereign level, Agna mirrors at the firm level—adopting the same foundations to structure and scale capital across global DeepTech ecosystems.

With this licence, we are accelerating our roadmap to unlock new channels across the East–West corridor, bridging mandates across frontier tech ecosystems in the USA, Europe, and India, with the Middle East as our fulcrum and vantage point.

Our investment theses, shaped over the past two years, are now entering the execution phase across Aerospace, Climate Tech, Life Sciences, and National Security. As operationalisation progresses, we remain committed to building the broader ecosystem through a disciplined and deeply thematic investment approach. These theses define our strategic architecture. More importantly, they serve as live instruments that guide where and how we catalyse next.

We partner with founders, institutions, and sovereigns to build the infrastructure DeepTech requires. This includes execution platforms, regulatory clarity, and sovereign-aligned operating models.

This is where our method takes shape: disciplined, future-oriented, and built for global scale.

This is Agna. Empowering the audacious.

Agna Updates

- In our recent LinkedIn post, we covered how the UAE is transforming into a DeepTech powerhouse with a USD 100B sovereign AI fund and foundational models like Falcon 180B. We also explored how Agna is building an East-West corridor to invest where emerging technologies meet emerging markets.

- In another update, we explored how Gulf nations are deploying capital as diplomacy, shaping trillion-dollar alliances in tech and infrastructure with the U.S. and UK. Agna stands at the intersection of this new economic order, activating the East-West corridor from its regulatory base in DIFC.

Listen to this Museletter

Questions? Feedback? Different perspective?

We invite you to engage with us and collaborate.

Warm Regards,

Team Agna

Click below to join our mailing list for The Agna Museletter.

Agna Capital Limited is regulated by the Dubai Financial Services Authority